The True Father of Artificial Intelligence

History does not always make things easy for geniuses. When John McCarthy (1927-2011) was born in Boston on the eve of the Great Recession to a humble family of European immigrants, little seemed to presage that this child prodigy was to become a worthy successor to Alan Turing. The delicate health of John’s little brother led the McCarthy family, who roamed the country in search of work opportunities, to settle in Los Angeles. It was there that John, a teenager already outstanding in mathematics, came into contact with the California Institute of Technology, Caltech, and taught himself college level mathematics after asking for their used textbooks.

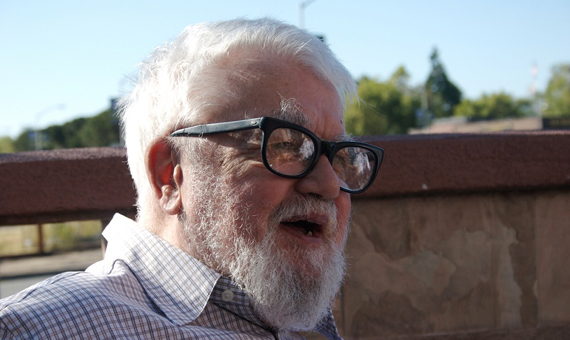

ohn McCarthy, father of artificial intelligence, in 2006, five years before his death. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

The future father of artificial intelligence tried to study while also working as a carpenter, fisherman and inventor (he devised a hydraulic orange-squeezer, among other things) to help his family. When he officially entered Caltech to study mathematics, he had already studied so much on his own that he was allowed to skip the first two courses. He graduated in 1948 and obtained his doctorate, also in the same field, in 1951 at Princeton. So far McCarthy’s career was just a little faster than normal, but he already had in mind his great obsession: machine intelligence.

In 1956, John organized the mythic Dartmouth conference where, in his talk, he first coined the term “artificial intelligenceâ€, defined as the science and engineering of making intelligent machines. There he established the objectives that he would pursue throughout his career:

“This research will proceed on the basis that every aspect of learning or feature of intelligence can, in principle, be described so accurately that you can create a machine that simulates them.â€

A legend for programmers and hackers

The inaugural text was written with Marvin Minsky and Claude Shannon, two prestigious scientists who soon abandoned the study of this field to direct their attention towards computation or mathematical theorizing. However, McCarthy is enshrined as the father of artificial intelligence not only for managing to open the field and turn it into a new area of research, but also for continuing to provide evidence for its development for half a century.

In the following years, McCarthy dedicated himself to sowing artificial intelligence laboratories in the best universities, a job that continues to give results today. He was infected with an unshakeable optimism and was convinced that he could get machines to think. “The speed and memory capacity of today’s computers may be insufficient to stimulate many of the more complex functions of the human brain, but the main obstacle is not the lack of capacity of the machines, but our inability to write programs that take full advantage of what we have,†he came to enunciate in those years.

McCarthy creÃa que las máquinas podÃan replicar la inteligencia humana. Crédito: Héctor Pasquariello

He himself sought the solution to his problem and created Lisp, the second oldest high level programming language that exists. Lisp was one of the favourite languages of the original hackers, with which they tried to make the primitive IBM machines of the late 1950s play chess. Perhaps this is why mastering this language is so highly respected in the hierarchy of programmers. This system was necessary for the development of McCarthy’s other great contribution: the idea of computer time-sharing, known as utility computing. In an era in which the personal computer seemed science fiction, John devised the theory of a super central computer to which many people could connect at once. It was one of the pillars of the future creation of the Internet.

Suspense in the Turing test

However, despite his efforts, this system did not help McCarthy to achieve his true objective: that a computer would pass the Turing test, according to which a human asks questions through a computer screen, and if he cannot decide whether it’s another human or a machine that is responding, this is definitively intelligent. For now, no computer has achieved it. “He believed that artificial intelligence consisted in creating a machine that could actually replicate human intelligence“, said researcher Daphne Koller, at the Artificial Intelligence Laboratory of Stanford University (California), where McCarthy worked for almost 40 years. Therefore, the computer scientist rejected most of the applications of artificial intelligence currently developed, which are directed solely at machines that imitate behaviour, but don’t learn.

Near the end of the research stage of his career, in 1978, McCarthy had to give up on his purist idea of artificial intelligence: “To succeed, artificial intelligence needs 1.7 Einsteins, two Maxwells five Faradays and the funding of 0.3 Manhattan Projects,†he resignedly recognized.

By Beatriz Guillén Torres for Ventana al Conocimiento

@BeaGTorres

Source: OpenMind