What can a Smartwatch do for your Health?

Tech giants have commited themselves to making 2015 the year of wearable technology. During the first few months of this year, they’ve been introducing a wide array of wearable devices, such as smartwatches and smartbands. Most of these innovative devices have one thing in common: they try to seduce consumers by promising a healthier and more active life.

Users can now find out, with increasing precision, how many steps they take every day, the calories they burn, the miles they run or swim, the time they spend sleeping, or have a register of their pulse rate. But well beyond the use people can find for this data, there’s another possibility that hast just come forth: donating this data to science. And this could very well stir up medical research and clinical trials. In addition to personal motivations, users can actively participate in studies to improve public health.

Smartwatches help motivate users to sit less and get more exercise

The underlying technology was already there, thanks to Big Data and mobile phones. In fact wearables have yet to prove themselves to be more precise than smartphones when tracking physical activity. Or so reads a University of Pennsylvania research study, comparing 2014’s most popular phones (iPhone 5S and Galaxy S4) with fitness-oriented smartbands (like Nike FuelBand, Jawbone UP and Fitbit Flex). The study’s authors question the need to invest in a new gadget. They argue that latest-generation phones, already so widely distributed (more than 65% of adults in the US own a smartphone), are a much better solution for physical activity and basic health data monitoring.

Last year, companies such as WebMD launched new services to help translate all that biometric data into useful information for the end user. Thanks to an app, the data compiled by the phone itself or by a paired device (such as a smartband, wireless weight scale or glucose monitor) is sent to health professionals who are capable of analyzing that data and who then recommend measures for the patient to take. Health objectives and actions are established from within the app. This initiative could appeal to anyone with an interest in a healthier lifestyle or, more specifically, to patients who suffer from chronic illnesses like diabetes type II or obesity. These patients need closer health status monitoring and the study of their biometric data could allow physicians to foresee their crises.

WebMD’s Healthy Target program also cleared a new path: once a patient hands over her biometric data to a platform, which treats it anonymously and ensures confidentiality, this data acquires a new value that goes beyond individual use for the patient’s treatment. Data analysis on a massive scale, with millions of smartphone users connected to a medical program, could offer revealing new patterns that could improve our understanding of diabetes, obesity and other diseases.

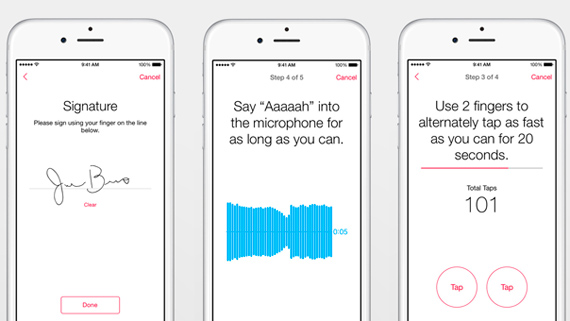

Screenshots of first ResearchKit apps

Apple became the first tech giant to move in this direction, with an ambitious initiative that may have been eclipsed by their own smartwatch’s launch. On March 9th, the same day the Apple Watch was presented, the company announced ResearchKit, a new platform that allows the 700 million iPhone users worldwide to participate in clinical trials and medical studies, providing data compiled through their phones or external devices connected to them.

The introduction of this medical research platform, as well as the first apps that use it is, according to some analysts, much more relevant than the Apple Watch itself. Apple partnered with first-rate medical centers to develop five programs that are already compiling data and conducting surveys on asthma, Parkinson’s, diabetes, breast cancer or cardiovascular disease. In exchange for their data, volunteers participating in the studies receive useful information: for example, people with asthma are informed of the areas in their cities where air quality is worse.

Despite being an open source initiative, ResearchKit is still limited to iOS devices, thus excluding Android users from participating in these studies. This introduces an important bias to be taken into account when analyzing data.

Moreover, when ResearchKit was opened in April 2015 to any institution, pharmaceutical lab or doctor willing to use it for purposes of scientific research, developers then discovered how easy it was for minors to join medical studies without parental consent, which is a legal prerequisite. Apple later modified the requirements to include parental consent as well as the approval of an independent ethics committee.

Preliminary data from a study on asthma carried out by Mount Sinai Hospital in New York are quite optimistic on the level of engagement of users. During the first weeks of the study patients used the app almost as frequently as social media.

Data safety in these medical programs is also a concern since, once again, technological possibilities progress faster than the reference legal framework. And like any technology set on granting the anonymity of the data it handles, it faces the possibility of security breaches. Users yielding their data for such studies will always face a certain risk of it being used for undesired purposes, or even against them.

Meanwhile, the first use of this biometric data in a courtroom has proven positive for a Canadian car accident victim who fights for compensation. The attorneys are using data compiled by a smartband to demonstrate how the accident’s sequels impair their client’s life. They use Vivametrica, a platform that processes public research data, to compare her physical activity pattern with that of the general population.

By Francisco Doménech for Ventana al Conocimiento

Source: OpenMind